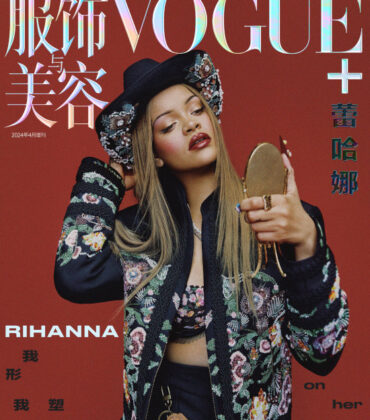

I have nothing but love for Lil’ Kim, but every time I see her trending on social media, I’m afraid to click the hashtag. As I watched her name soar to the top of Twitter last night, I knew that whatever had caused this, it probably wasn’t going to be good. And, of course, I was right. I was immediately faced with a bunch of screenshots of an unrecognizable collage of images of Kim, that she had uploaded to Instagram herself. This isn’t the first time we’ve gotten a terrifying glimpse into Kim’s ongoing transformation, but this image was particularly egregious. The truth of that matter is, however, if we had been paying attention all these years, we really shouldn’t be so shocked.

“All my life men have told me I wasn’t pretty enough — even the men I was dating. And I’d be like, ‘Well, why are you with me, then?’ ” Kim said in a 2000 interview with Newsweek. “It’s always been men putting me down just like my dad. To this day when someone says I’m cute, I can’t see it. I don’t see it no matter what anybody says.”

With just a few words, the rapper communicates a lifetime of trauma. She’s no longer an icon, of glitz, glamour, multicolored wigs, bravado, and sexy lyrics, she’s just Kim. She’s any one of us. We’ve all had moments like these, maybe more so than many of us are willing to admit.

Kim has always been candid about how colorism at the hands of black men affected her. bell hooks writes, in Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-Esteem,

Speaking about her career as a rapper in Essence, the magazine for “Today’s Black Woman,” Lil’ Kim acknowledges: “When I was younger all the men liked the same women: those light-skinned European-looking girls. Being the rapper Lil’ Kim has helped me to deal with it a little better because I get to dress up in expensive clothes and look like a movie star. All the people responding to me has helped. Because I still don’t see what they see.”

I’ve been complimented by being told that I’m “not that dark,” and put down by being told that I’m not worthy of anyone’s wife.

I’ve had my racial background interrogated in a desperate search to find the one exotic drop of blood that would make my blackness palatable.

I’ve been compared to cousins, friends, acquaintances, actors, singers, models, and even imaginary women — with anything ranging from a backhanded compliment to a veiled insult.

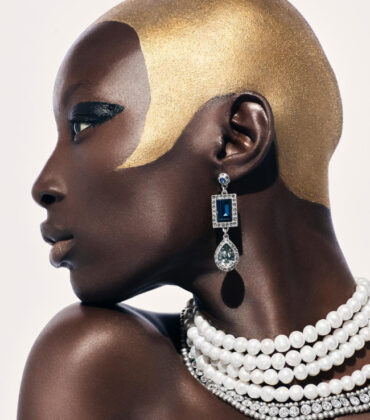

To be beautiful as a black woman in Western society is to know that your specific set of features always comes with an asterisk, an addendum, and a footnote. It is to be beautiful despite our blackness but not because of it. To be beautiful as a black woman is to have every strand of hair and every pore expertly dissected and graded on an arbitrary scale that shifts with the wind.

To be beautiful as black women, means to have eyes from one country, a nose from another, hair from one continent, cheekbones from one ethnic group, a body from a collection of different peoples, a skin tone from one place, and an eye color from another. All of these requirements are laid out in hopes that we’ll occupy a space on a totem pole informed by Western beauty standards. If we’re lucky we can float around the middle of that totem pole. If we’re really lucky we can be above the middle. But no matter where we stand, the weight of whiteness crushes our backs.

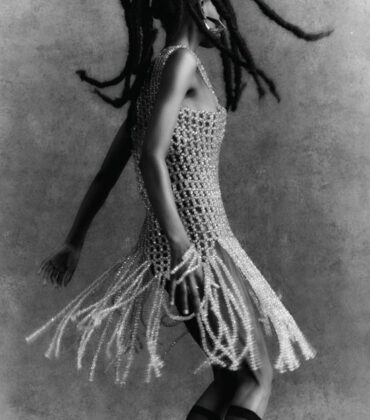

With each trauma the weight gets heavier. For those of us who have our beauty affirmed in one way or another, it becomes easier to shift weight. Those of us who can develop the strength to keep going, we can even unload a weight. But what happens when we just keep carrying a heavier load?

So many black women and girls carry the scars of a particular kind of trauma. The trauma that comes the moment we realize that the physical differences between ourselves and “other” girls are more than arbitrary. This trauma comes from knowing that girls that look “like us” will never cover a magazine or get the guy in our favorite movie. The pain is exacerbated when girls that look “like us” finally gain representation, but it becomes immediately apparent those girls don’t really look “like us.”

Unlike Lil’ Kim, the average black woman doesn’t have access to millions of dollars and resources to change our faces and skin tones. But what if we did? What would happen? How many of us would undergo a dramatic “transformation” after years of criticism and personal slights?

There’s a stigma against plastic surgery in the black community. Call it the Michael Jackson affect. It’s not only a fear of becoming something unnatural, but also a fear of wearing your self-hate on your sleeve. Pride, specifically black pride is a benchmark of African-American culture. Looking like Michael Jackson or Lil’ Kim is an admission that your pride is a lie.

But how many lies do we tell ourselves and others to maintain the appearance of unity? Colorism, is something that often feel a need to keep quiet about — so much so that those of us who are disadvantaged the most are made to hold in our pain.

In one of her first post-prison interviews, back in 2006, Lil’ Kim denied that her changing appearance was due to self-hate. Instead she maintained it was a result of her vanity.

“I love myself,” she said. “There’s certain things that I was obsessive with. People think that I did it because I had low self-esteem. But that wasn’t the case. I think I did it because I was a little too vain. […] I’m a perfectionist.”

Earlier in the interview, however, Lil’ Kim admitted to being a survivor of domestic violence, an experience that she said shared with her fans so that they would understand that she too was human.

“I shared that story ‘cause people think that once celebrities, especially females, get into the industry, they feel like we’re so different. I just wanted females to know that I went through the same thing while I was some people’s role models — and I was Lil’ Kim.”

“We the same people — just like y’all. I got feelings — just like y’all. Same people. I bleed just like y’all. Same people. I got feelings just like y’all. And that’s the whole thing. We still at the end of the day human.”