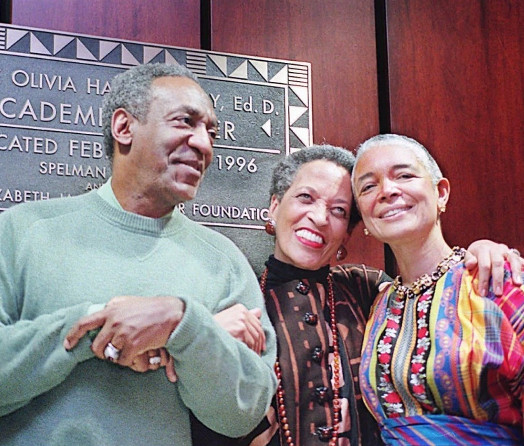

Bill and Camille Cosby with Johnetta B. Cole in 1996. (AP Photo/Atlanta Journal Constitution/W.A. Bridges Jr.)

The ongoing controversy surrounding the work, life, and legacy of Bill Cosby after 46 women have come forward to accuse the comedian of sexual assault, has opened up a lot of complex conversations.

The personal accounts of such a diverse group of women, as profiled in New York Magazine last week, serve as a jumping off point for larger discussions about rape culture, male privilege in Hollywood, and of course, race. The accusations against Cosby, undeniably go beyond skin color. But, his intrinsic association with the black community as black man who supported black people and causes, make cutting ties with Bill Cosby a very loaded issue for many institutions. The impact of the media representation that he created, over the years, as well as his philanthropic exploits alongside wife Camille, can’t be denied.

Last month, Spelman College, announced that it would be officially severing ties with Cosby, by ending a professorship funded by Bill and Camille Cosby.

The professorship was funded through an endowment created in the late 1980s, when Bill and Camille Cosby donated $20 million dollars to Spelman. At the time, it was the largest individual donation ever made to an historically black college or university (HBCU).

Spelman’s decision to end the 30-year relationship was made after a decade-old deposition was uncovered by the network, in which Cosby admitted to giving women drugs in order to have sex with them.

In addition to Spelman, media scrutiny has also been directed at the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art. Several works owned by the Cosby’s are currently on display in an exhibition, titled “Conversations.”

After months of speculation, director Johnetta B. Cole, who has known Bill and Camille Cosby since the 1970’s has broken her silence. In an essay for The Root, titled “Why I Kept Open an Exhibit Featuring Art Owned by Bill Cosby,” she explains her decision to keep the exhibition open in the midst of controversy.

Cole writes,

As someone deeply committed to human rights for all people, and especially because of my long-standing engagement with women’s issues, I am devastated by the allegations and revelations surrounding Bill Cosby. I must also say that in no way will I ever condone anyone committing sexual violence against women and girls.

More than 150,000 people have visited “Conversations” since it opened last November, and we expect thousands more to see the exhibition in the coming months. It is my responsibility as the museum’s director to defend the rights of the artists in “Conversations” to have their works seen. It is also my responsibility to defend the rights of the public to see these works of art, which have the power to inspire through the compelling stories they tell of the struggles and the triumphs of African-American people.

There are 171 artworks in the exhibition. Two-thirds are from our museum’s permanent collection, and about one-third are from the collection owned by Camille and Bill Cosby. Only five items—four quilts and a painting by one of the Cosbys’ daughters—relate to the Cosby family.

Throughout the exhibition, there are words from the curators, and in a few places the texts include words from the Cosbys, along with one image of them, that explain why their collection was assembled. Each text is offered to help visitors engage with the rich dialogue between the African and African-American artworks.

Cole also states that the Cosby’s made a donation of $716,000, a fact that she maintains she never tried to hide. She does admit, however, that she would not have accepted the donation or moved forward with the exhibition if she had been made aware of the allegations against Cosby earlier.

She also asserts that the exhibition, which highlights the work of many highly influential African-American artists such as Elizabeth Catlett and Lois Mailou Jones, “remains open because art speaks for itself, not its owners. And the African-American art in this exhibition has so much to say that has long been silenced.”

[…] of speculation, director Johnetta B. Cole, who has known Bill and Camille Cosby since the 1970’s, defended her choice to keep the exhibition open despite the […]