For the month of February, The New York Times is opening up its archives — revealing a massive collection of previously unpublished photos. According to the paper, the pictures are “Images from black history, drawn from old negatives, have long been buried in the yellowed envelopes and crowded bins of the New York Times archives.”

According to the Times, the images were not published as a result of a historically different media climate,

Were the photos — or the people in them — not deemed newsworthy enough? Did the images not arrive in time for publication? Were they pushed aside by words here at an institution long known as the Gray Lady?

More than now, we also put a premium back then on words, not pictures, which meant that many photographs that were taken were never published.

But other holes in coverage probably reflect the biases of some earlier editors at our news organization, long known as the newspaper of record. They and they alone determined who was newsworthy and who was not, at a time when black people were marginalized in society and in the media.

Check out a few images from the archive below and check back daily as the The Times will be updating the archive daily for the month of February.

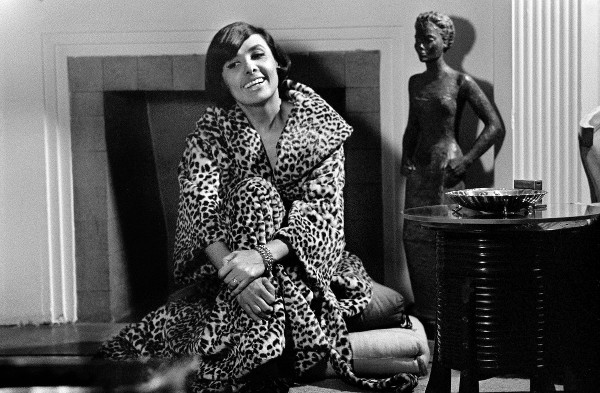

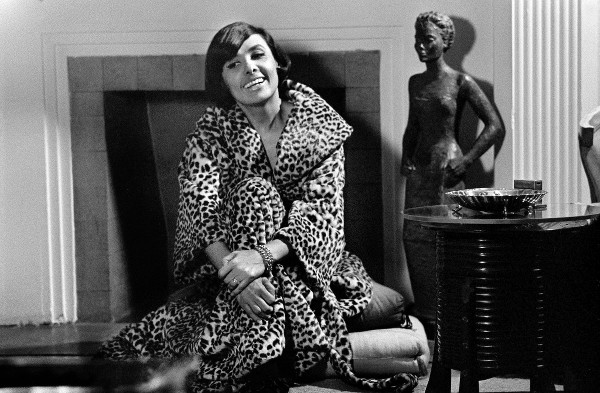

By Dec. 17, 1964, when this photograph was taken by our photographer, Sam Falk, Ms. Horne and her husband, Lennie Hayton, a white composer and conductor, were comfortably settled in. She was hanging Christmas decorations that day as she prepared for the debut of her television show, “Lena.”

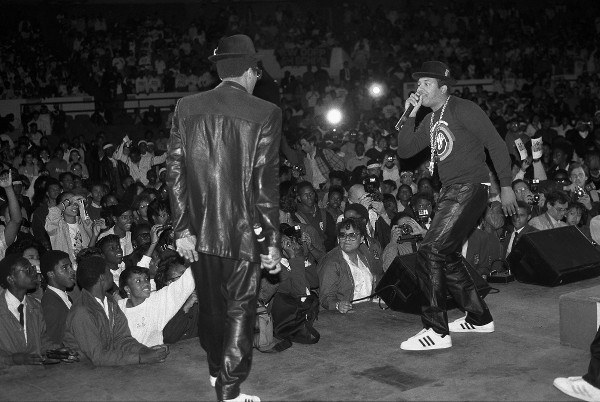

Chester Higgins Jr. spent 40 years as a staff photographer for The Times before retiring in 2014. Writing from Ethiopia, he described covering Run-DMC at Madison Square Garden in 1986 for a benefit concert against crack cocaine. We never published photographs from the show or wrote about the performance.

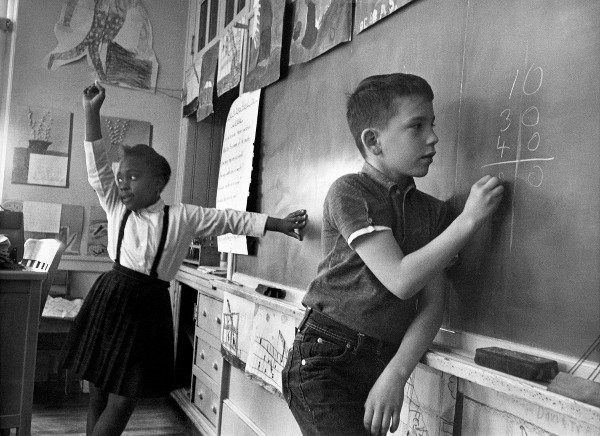

An article in The Times Magazine — with a picture showing high school students in Princeton, N.J., between classes — assessed the school system’s progress in integration, which was trumpeted as a model for struggling integration efforts in schools across the country. It also offered a caveat that still resonates, noting that in the search for a thriving and equal community, “good schooling is not enough.”

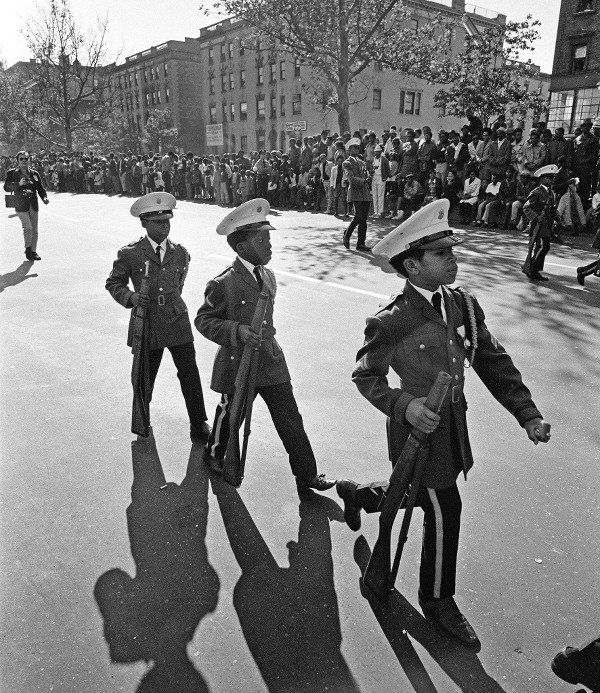

It was New York City’s first Afro-American Day parade, a moment of pride and solidarity, much needed in September 1969, after years of struggle and strife.

“A parade is not an end; it’s just a mechanism,” said Livingston L. Wingate of the United Federation of Black Community Organizations, which formed that year to address various concerns. “It is an attempt to utilize our numerical organizational strength,” he added. “I call it a massive computer system, programmed by the people of Harlem.”