Skin color, like height, hair color, hair length, hair texture and body weight are all gendered. Naturally, there are nuances and intersections within these standards of beauty. Men have to be tall, but women not too tall. If a woman is tall, she needs to compensate by being willowy or model-esque. Women are expected to have long hair, and men short hair, unless they are cultivating a rugged look in the vein of Jason Momoa (mmm) or Fabio (eh).

Just as height, hair and body weight are gendered, so is skin color. Colorism, like all Western beauty standards, is rooted in white supremacy and isn’t merely a beauty standard but a social one, that like racism, is systemic.

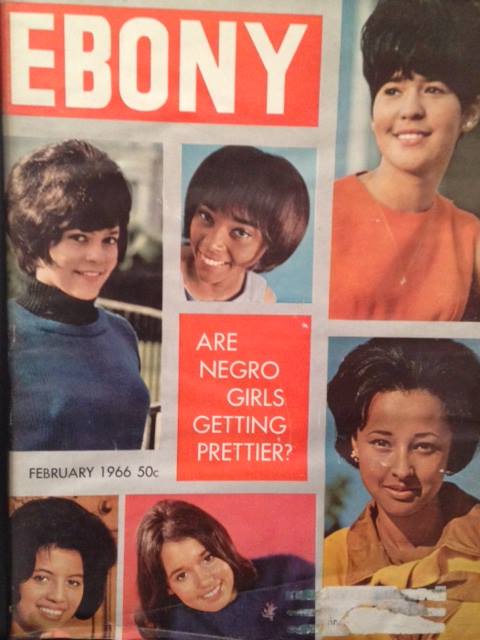

Images of lighter-skinned men and women being used to represent African-American aspirational beauty aren’t anything new, vintage issues of Jet and Ebony magazines will attest to this.

Historically, much of the wealth in the African-American community was held by lighter-skinned blacks, who even created organizations to exclude those who were darker. According to Marquita Golden, author of “Don’t Play in the Sun: One Woman’s Journey Through the Color Complex ”,

Back in the day there were paper bag tests, blue vein societies and the orthodoxy that AKAs are light, Deltas are brown, Zetas are black. Fast forward to today and on Twitter there is a #teamlightskinned hashtag and complexion competitions in urban nightclubs, as reported by the St. Louis American via the St. Louis-Post Dispatch. The color complex — or, put simply, the belief in the superiority of light skin and European-like hair and facial features — is, among African Americans, a legacy of slavery. Once practiced and adhered to with nearly unquestioned fidelity, today, despite its persistence, colorism is increasingly being questioned, and in some quarters dismantled.

While colorism increasingly is being questioned, critiqued and decried, the commodification of black masculinity with the rise of hip-hop music and the prominence of black male entertainers has caused a very blatant schism in the way colorism affects the lives of black women and black men. This split is especially apparent when looking intra-racially or simply turning on your television.

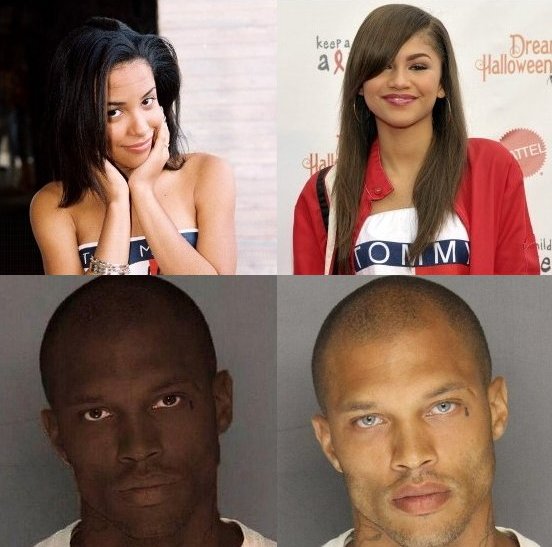

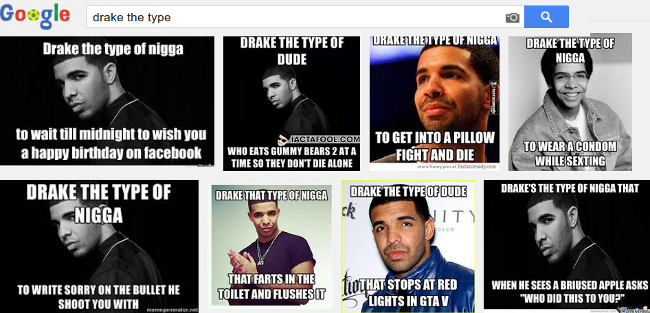

Many of the women presented as beautiful or placed at the forefront in media geared exclusively towards African-Americans tend to be lighter or racially ambiguous, a standard that definitely doesn’t persist for African-American men. Colorism also accounts for a disparity in marriage rates for women based on skin tone, meaning there are actual socio-economic implications for black women as a result of colorism in African-American communities. This disparity isn’t comparable to any disdain that lighter-skinned men might experience. Darker complected women are often degraded and devalued, while lighter men simply become memes.

In the larger social structure of the United States, the effects of colorism become more dire. Colorism affects incarceration rates, the length of sentences, the overall likelihood of being accused of or charged with a crime, and the ability to obtain leadership positions for both African-American men and women in professional settings.

This brings us to two stories which have firing up the interwebs in the past week, Zendaya Coleman being cast to play Aaliyah in an upcoming biopic and Jeremy Meeks, a super sexy felon.

I’m not personally riled up over her casting, but I understand how colorism could play a role in Zendaya being cast to play Aaliyah. Many of her supporters are comparing her taking on the role to Denzel Washington playing Malcolm X, Will Smith playing Muhammed Ali, Jamie Fox playing Ray Charles, and Angela Bassett playing Tina Turner. Notice, this list is mostly men.

In reality, this situation is actually a bit closer to Zoe Saldana playing Nina Simone, but nowhere near as severe, as no prosthetics and dark make-up haven’t come into play.

Either way, hardcore Aaliyah fans are upset, and most of the rebuttals, like the above examples, are false equivalences that don’t take gendered colorism into account.

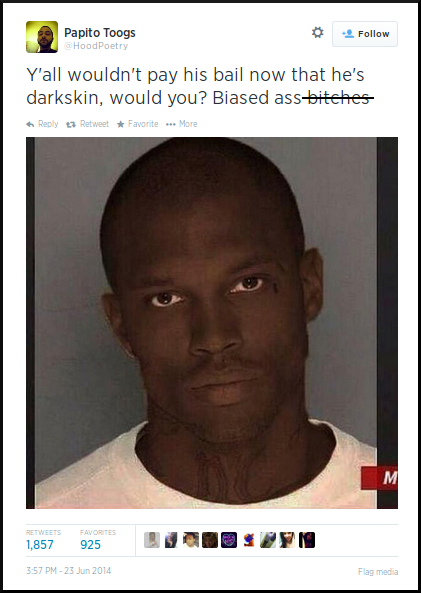

When we take colorism out of the free world, we meet Jeremy Meeks, the man, the myth, the mugshot. His, now viral, image and the myriad responses to it have been hotly debated, particularly by many a misogynist or simply a holier-than-thou individual. For some it’s an “Aha!” moment, an unmasking, proof that black women can be just as colorist as some black men, ignoring that most of his admirers aren’t African-American women.

This argument rests of the false idea that the desires and attractions of women are treated and regarded equally to those of men, in society. But, none of us ogle in a vacuum, and discussions of media representation, like all else, need to be intersectional ones.

The Jeremy Meeks’ and the Michael Ealy’s of the world can co-exist peacefully with the Idris Elba’s and Taye Diggs’. This harmony is not simply because women are petty and insecure, but because skin color is gendered and colorism is a gender issue.

Hi…like your webpage….well…the fashion and art offerings…anyway. The truth about colorism is that it has everything to do with money…and control and nothing to do with beauty. The light skin male vs. dark skin male thing can be challenged with the fact Brian Nichols (Atlanta convict who shot a judge and court reporter) was also “wooo-ed” over….by many women and the whispers here is he gets “special” treatment to this day ….I guess cause he’s so fine. and Brian Nichols is Dark Skin….so is Denzel, Idris Elba, Tyson Beckford….and the list goes on. Colorism is nothing more than a way to keep money out of our community. Thats the real reason a African American woman can’t play an African American woman in 2014. When black women are doing well …then so will our community. Nope, just cause Michael Jordan is rich that doesn’t mean black ppl are doing well. His family is not black and he’s not active in our community. so please. His personal wealth ..is his personal wealth. So, lets call it what it is.

Oh, and by the way there is a difference between being “light skin” African American and being Bi-racial. let’s call that what it is too. and anyway….this was all planned out in that Willie Lynch letter ..now wasn’t it.

And for the record….when you read those comments and Mr. “I Got Them Guns”Meeks….most of those women commenting were latina…so cut the crap.

[…] included in the upcoming TV movie, doesn’t bode well for the film. Ongoing discussion about colorism in the casting of Aaliyah, as well Missy Elliot and Timbaland, have also added more controversy to […]

I’ve been saying this for years