(The results of a Google search for “multicultural hair care.”)

Beauty brands are already bracing themselves for 2042, the magical year when, according to census projections, whites will no longer be the majority in the United States. These projections cite immigration, and interracial relationships as key factors in demographics shifts. Multicultural and “ethnic” beauty brands are already providing formidable competition to so-called mainstream brands, with such brands seeing a 3.7% increase in 2014, according to research by global consulting and research firm Kline & Company.

Kline & Company lists brands such as Carol’s Daughter and Shea Moisture as previously exclusive brands which are now rebranding to reach more customers with more “inclusive” marketing campaigns.

When Carol’s Daughter announced its acquisition by L’Oréal USA last fall, hot on the heels of news that the brand’s stores would be filing for bankruptcy, the revelation opened old wounds for many faithful black female consumers. In 2011, Carol’s Daughter faced accusations of colorism when it rolled out a new marketing campaign starring model Selita Ebanks and musicians Solange and Cassie, all relatively lighter complexioned women, two of whom were sporting straightened hair.

The brand responded to criticism in a press release with a statement from CEO Steve Stoute, which seemed to add more fuel to the fire,

We want to be the first beauty brand that truly captures the beauty of the tapestry of skin types in America. When I say polyethnic, I mean women who are made up of several ethnicities. If you ask them what they are, they’re going to use a lot of different words to describe themselves. That’s in line with the Census data coming out — people are checking much more than two boxes. We believe we’ve put together a shoot that celebrates many different ethnicities, to become a mirror of what America’s really becoming.[…]“They will serve as cultural ambassadors in bringing forth this acceptance that the definition of beauty is now colorless.

The statement rubbed many former loyal consumers the wrong way, with some even calling for a boycott. How could a brand be truly inclusive when black women with darker skin and tighter coils are nowhere to be found?

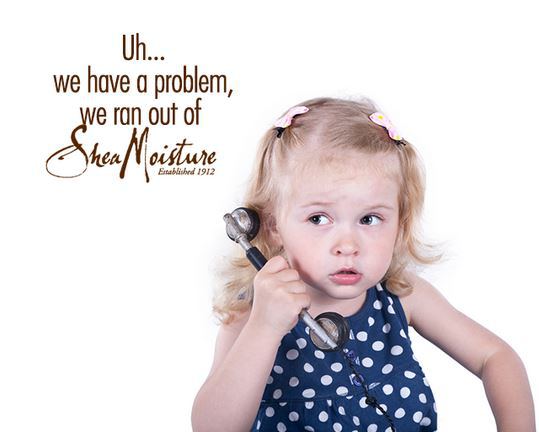

Beauty brand Shea Moisture recently ran into a controversy of its own when it sent out a meme tweet featuring a white child instead of a black one, causing social media followers and fans to question how black the brand actually is.

I hate that shea moisture went mainstream . 95% of hair products are made for non black women . Can we have something of our own ?

— Jan (@TheeJenBunny) February 23, 2015

Beauty and skincare giant Dove, which has been applauded for showcasing body diversity in it’s marketing campaigns, also pushed full-force into multicultural haircare marketing with it’s “Love Your Curls Campaign.”

But as writer Kinsey Clarke points out in For Harriet, the campaign appears to feature very few darker complexioned black women with tighter kinks and coils.

We know that Dove has a target audience and it is not us. The women and girls in the commercials and ads have loose ringlets and waves. The problem with this using these girls in a campaign about “loving your curls,” is that these girls will experience positive reinforcement about their hair textures. The video features mainly white and mixed race girls, with one black girl with a kinky hair texture. The girls who are mixed-race will eventually be told that they have “good hair.” The white girls will be told that their curls are cute and quirky. The girl with kinks will be one who catches the most negative reinforcement about her hair texture. Black women and girls with kinkier hair have been using the tools of satin bonnets and pillow cases to protect our hair since forever, but again we are excluded from the market that steals its ideas from us.

It’s pretty clear that natural hair care spaces served as inspiration for Dove’s new marketing kick. This highly-criticized ad features fashion blogger Emily Schuman, who has nearly straight hair, wearing her hair “naturally.”

Terms that were popularized in natural haircare spaces also appeared to be lost in translation in a now infamous interview which featured on natural haircare site Curly Nikki, featuring a white woman with 3-type hair talking about her “transition.”

The blurring of lines between mainstream and niche beauty spaces revolves around multinational beauty giants acquiring, controlling, and flat out “Columbising” independent beauty spaces — spaces that were originally created out of sheer need. But rather than satisfying needs, these brands seem to create new ones by touting one-size-fits-all beauty solutions. Terms like “women of color” and “ethnic” become meaningless buzzwords, which sound inclusive, but actually reduce the vast diversity of non-white women to a single faceless, race-less racial identity. Catch-all terms like “mixed” ignore the fact that mixed women of African descent still have to battle a complicated host of intersections, particularly anti-blackness. How can a consumer find products that meet their specific needs when brands don’t appear to want to define themselves?

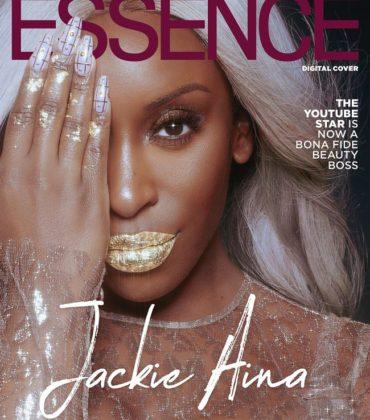

The brave, new, world of multicultural beauty marketing doesn’t only provide challenges to consumers but also to entrepreneurs. While black consumers purchase nine times more beauty products than their white counterparts, businesses owned by black women are growing exponentially. The natural hair movement created a new class of black women entrepreneurs and haircare gurus. Established beauty corporations can use everything from name recognition to large monetary investments to edge out independent brands and block them from accessing certain marketing and distribution channels.

Additionally, the core message of the Natural Hair Care movement, loving your hair as it is, isn’t particularly useful to major corporations who need repeat customers. Even “inclusive” companies still hide subtle messages in their marketing to convince 4c’s that they really need to be 3c’s ,and 3c’s that they really need to be 2c’s — in order to keep them buying more product. If brands were truly invested in inclusivity, they would alter their existing product lines rather than creating new ones or acquiring new lines and then drastically changing them.

While the natural hair movement was all about finding solutions and alternatives, the new, inclusive movement seems to raise more questions. Who’s really being included?

[…] consumer, essentially leaving black buyer behind. Shea Moisture has been criticized in the past for using images of white models on its social media pages. The company also dogged accusations of being in bed with Mitt Romney. […]