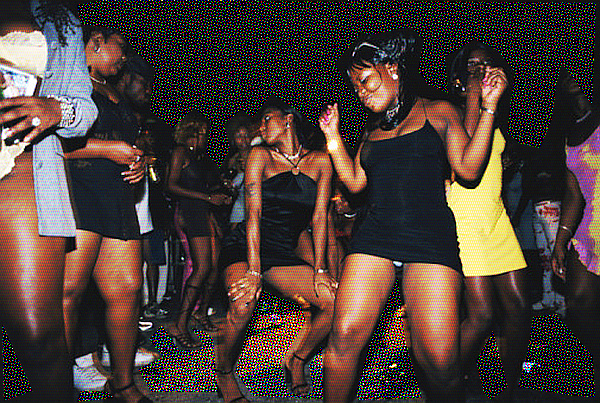

(Christopher Pillitz / Photonica World)

A friend recently asked me whether I listen to reggae and dancehall music and if so, which artists I enjoy listening to. My response was that I do listen to reggae and dancehall, mostly old school reggae but my answer was short and I believe I gave her an inadequate explanation as to why I continue to listen to those genres. Dancehall, more so than reggae, is especially violent, homophobic, and serially objectifies women. What I should have told my friend, is that the topic is as nuanced and complicated, as hip-hop’s relationship to black women and feminists. Michelle Denise Jackson recently pinned a piece over at For Harriet about her love of ratchet music, while still subscribing to feminist ideals. Issa Rae creator of Awkward Black Girl, isn’t quiet about her love of everything ratchet as it relates to hip-hop and reality television. Even Tracy Ellis Ross of Girlfriends and Black-ish has a love-hate relationship with the polarizing genre. Similarly to these ladies, I enjoy a wide range of reggae and dancehall music but navigating through the murky waters can be a bit complicated. To say I totally abstain would be complete hypocrisy, and I try to live as authentically as possible, even when there are eyebrow-raising contradictions.

My Love Affair With Reggae and Dancehall

My love affair with music, particularly reggae and dancehall, started at an early age. I grew up in a Pentecostal household in Jamaica, in which it was seen as “ungodly” to listen to “the devil’s music,” so naturally, like most young people growing up in church, I was curious about the prohibited and appeased my curiosity whenever I was outside the home. Reggae and dancehall music are ubiquitous in Jamaica. I had my fill in taxis and buses on the way to school and our neighbors BLASTED music every weekend from Friday through Sunday. Songs like Beres Hammond’s – “Pride & Joy,” Garnett Silk’s- “Oh Me Oh My,” “Hello Mama Africa,” and a host of songs from 90’s-singer Sanchez were among my favorites growing up. As I got older, my taste widened and I came to love bands like UB40, legendary singer Bob Marley, and the smooth sounds of Maxi Priest. I also really dug Sean Paul and his music was a fixture that got me in the zone before my high school basketball games. On one of my latest trips to Jamaica, I was introduced to some more recent dancehall songs. While on our way to a party, my cousin blasted a host of dancehall artists from his car speakers. I enjoyed listening to tracks like, Wayne Wonder’s “No Letting Go,” Demarco’s “I Love My Life,” and Popcaan “Party Shot.” The electrifying sounds coupled with my Red Stripe and rum buzz while the cool night air hit my face was pure ecstasy.

In a recent NPR interview, Solange Knowles chatted about hip-hop and her love for the genre. She talked about her love of Nas, early Cash Money and a plethora of other rap artists. A question was posed in the interview about when the music gets to be “too much.” And by this the interviewer was specifically addressing issues like the objectification of women, violent lyrics and among other problematic issues associated with the genre. Interviewer Ali Shaheed Muhammad, formerly of A Tribe Called Quest, cited Dr. Dre’s song, “Xxplosive,” as his “I can only take so much” track. He states, “Such a great sounding record but lyrically — I don’t know, it pushes against me a little bit too much.” Solange’s take on the issue is summed up in the following statement: “Well, I mean, there’s definitely truth to a lot of those stories which you can’t deny and disassociate from, which is the way that I try to look at it — that’s a lot of people’s truth. That’s a lot of people’s environment, whether it’s right or wrong. As an artist, everybody has the opportunity to celebrate and speak their truth.” This is precisely where I stand with some, certainly not all, of reggae and dancehall music.

Where We Come From

Like hip-hop, dancehall and reggae was birthed out of the ghettos — hip-hop started in the Bronx, New York and reggae and dancehall from impoverished neighborhoods in Kingston, Jamaica. From the get go, both mediums set out to verbalize the social and economic injustices of everyday people. Carolyn Cooper, author of Sound Clash: Jamaican Dancehall Culture At Large States, in Jamaica, states that reggae and dancehall were ways of “defying the Eurocentric values of respectability.” This is evident in Popcaan’s song, “Where We Come From.” In the song, the young artist talks about the struggles of poverty, the experience of having a friend murdered, and how he ignored nay-sayers to push through, even when the odds were against him. Jamaica is a third-world country. There’s hardly a middle class — you are either filthy rich or very poor, and unfortunately there are many though ghettos that house the less affluent. So when Popcaan croons about never forgetting where he comes from, I totally relate, although I wouldn’t categorize myself as a “thug” as the artists self-identifies throughout the song.

I had a mixed bag of experiences and lived all over the island of Jamaica before I migrated to Georgia at ten years old. I got my street education from living in Flankers, Montego Bay — one of the most dangerous “hoods” in Jamaica. We heard gun shots on the regular, my best playmate’s mom was a well-known prostitute, and bloody and violent altercations weren’t uncommon. Like Popcaan, I will never forget where I come from. My deep Jamaican roots and varied experiences have shaped my worldview. Listening to these songs brings back memories of my childhood on the island. Songs like “Summertime” by dancehall artist Vybz Kartel’s, remind me of the glorious summers spent with a host of my cousins and siblings in the deep Jamaican countryside. My summers were spent freely roaming the hills picking fruit, soaking in the river (some of us couldn’t swim), and enjoying everyone’s company — from my twin great uncles who always brought us treats, to our grandmother, who always had three meals prepared everyday for us kids (how did she do it?). My great grandmother, granny she was called — her loving hugs and wise words continue to warm my spirit. So much love, quality time spent, and fond memories. These experiences and more have shaped how I continue to view family and familial bonds. So when Vybz sings, “Summer time inna Portmore/Summer time inna Kingston/Summer time inna Country/Summer time inna my scheme,” he evokes a feeling of nostalgia and familiarity that I can’t help but connect to. Other songs like “Party Shot,” “One by One,” and Major Lazer’s, “You’re No Good For Me,” are fun songs that are in no way offensive or demeaning.

Push back when necessary

With all that said like Solange and Ali, I do have my limits. While much of the reggae music I listen to is connected to a sense of nostalgia, there are songs and artists that often give me pause as a listener. Songs like, “Boom Bye Bye” by Buju Banton and artist Tommy Lee Sparta are like fire to my ear drums. Navigating the reggae and dancehall world can be difficult, uncomfortable, and troublesome at times. But, reggae and dancehall will forever be a part of the Jamaican culture, as I will forever be a Jamaican by birth. Even the language used in reggae and dancehall (patios or patwa) represents a push back of the colonial English that was brought to the country during slavery. As author Carolyn Cooper again states, when juxtaposing the musical genres to Karl Marx’s quote, “religion is the opium of the mass,” she asserts then that “reggae is the ganja of the massive.” I definitely do not hold the same values and sentiments as some of these artists but there’s genuine love for the music and furthermore I won’t subscribe to respectability politics that suggests what is or isn’t “respectable” music. Neither, will I hold a Eurocentric attitude that labels the culture of dancehall as “backwards” or “uncultured.” This isn’t to say that a healthy dose of awareness isn’t necessary. It’s all about comfort levels and doing what’s right for you.

[…] previously shared my relationship with reggae music, particularly dancehall and its contradictions. Over the weekend I relished in a few videos that highlighted the resurgence […]

Well written, and I totally agree!! I have the same polarizing views but must admit Dancehall (old and new) is my favorite genre of all time!